St. Valerian, Niacrinus, & Gordian

Death: unknown

Confessor and brother of Sts. Ambrose and Marcellina. Born at Trier, Germany, he moved to Rome with his family and was subsequently trained as a lawyer. Appointed prefect to one of the Roman provinces, he resigned his post when Ambrose became archbishop of Milan in order to assume administration of the secular affairs of the archdiocese. He died unexpectedly at Milan and was eulogized by his brother with the funeral sermon, "On the death of a brother."

Saint Satyrus of Milan (Italian: San Satiro) was the confessor and brother of Saints Ambrose and Marcellina. He was born around 331 at Trier, Germany, moved to Rome with his family and was subsequently trained as a lawyer.

Appointed prefect to one of the Roman provinces, he resigned his post when Ambrose became Archbishop of Milan in order to assume administration of the secular affairs of the archdiocese.

He died unexpectedly at Milan in 378 and was eulogised by his brother with the funeral sermon, On the Death of a Brother (De excessu fratris Satyri). The church of Santa Maria presso San Satiroin Milan refers to him.[1]

He should not be confused with the bishop Satyrus of Arezzo.

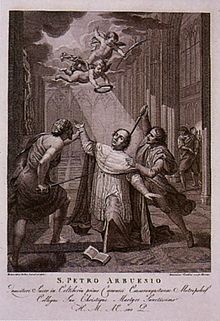

Augustinian inquisitor. He was born in Aragon, Spain, and became a master of Canon Law at the University of Bolognabefore becoming an Augustinian canonat Saragossa in 1478. In 1484 he received appointment as Inquisitor of Aragon and soon earned the enmity of the Marranos, Jews who had been forcibly converted to Catholicism. Peter was murdered by a group of Marranos in the cathedral of Saragossa. His name has been associated with acts of wanton cruelty and inhumanity in the fulfillment of his office as Inquisitor, although these have never been substantiated.

Pedro de Arbués (c. 1441 – 17 September 1485) was a Spanish Roman Catholic priest and a professed Augustinian canon.[2] He served as an official of the Spanish Inquisition until he was assassinated in the La Seo Cathedral in Zaragoza in 1485 allegedly by Jews and conversos.[3] The veneration of him came swiftly through popular acclaim. His death greatly assisted the Inquisitor-General Tomás de Torquemada's campaign against hereticsand crypto-Jews.

His canonization was celebrated on 29 June 1867.[4]

Pedro de Arbués was born at Épila in the region of Zaragoza to the noblemanAntonio de Arbués and Sancia Ruiz.[4]

He studied philosophy perhaps in Huesca but later travelled to Bologna on a scholarship to the Spanish College of Saint Clement which was part of the Bologna college. He obtained his doctorate in 1473 while he served as a professor of moral philosophical studies or ethics.[3] Upon his return to Spain he became a member of the cathedral chapter of the canons regular at La Seo where he made his religious professionin 1474.[2][4]

At around that time Ferdinand and Isabella had obtained from Pope Sixtus IV a papal bull to establish in their kingdom a tribunal for searching out heretics. Those Jews who had received baptism were known as conversos; some might have continued to practice Judaism in secret.[3][4] Tomás de Torquemada was in 1483 appointed as the Grand Inquisitor for Castile. He then appointed Arbués and Pedro Gaspar Juglar as Inquisitors Provincial in the Kingdom of Aragon on 4 May 1484. Their work was opposed by converts and people who saw it as a threat to their freedoms.[3][2]

On 14 September 1485 Pedro was attacked in the cathedral as he knelt before the altar and had been wearing armour since he knew his work posed great risks.[3] Despite wearing a helmet and chain mail he died from his wounds on 17 September. His remains were entombed in a special chapel dedicated to him.[2]

The Inquisition was opposed in Aragonas it was seen as an imperial attack on the charters, privileges and local laws. The most powerful families among the converted Jews: the Sánchez, Montesa, Paterno and Santangel families seem to have been involved in the murder.[4]

As a result, a popular movement against the Jews arose in which nine were executed, two killed themselves, thirteen were burnt in effigy, and four punished for complicity, from 30 June to 15 December 1486, according to the historian Jerónimo Zurita. Leonardo Sciascia in Morte dell'inquisitore (1964) writes that Arbués along with Juan Lopez Cisneros (d. 1657) are "the only two cases of inquisitors who died assassinated".[4][5]

Pope Alexander VII beatified the late priest in Rome on 20 April 1664.

His canonization was celebrated on 29 June 1867 among protests from Jews and Christians. Pope Pius IX said in the document formalizing the canonization (Maiorem caritatem): "The divine wisdom has arranged that in these sad days, when Jews help the enemies of the church with their books and money, this decree of sanctity has been brought to fulfillment

Bishop, martyr, and patron of St. Willibrord's missions. He was the son of a noble family of Maastricht, Flanders, Belgium, educated by St. Theodard and succeeding him as bishop of Tongres-Maastricht in 668 when Theodard was murdered. He was driven from his see by Ebroin, the tyrannical mayor of the royal palace, and lived as a Benedictine in Stavelot until 681, when he was reinstated. When Lambert denounced the Mayor of the Palace Pepin of Heristal for adultery, he was murdered in Liege, Belgium.

Saint Lambert or Lambrecht of Maastricht (Latin: Landebertus/Lambertus; c. 636 – c. 705) was the bishop of Maastricht-Liège(Tongeren) from about 670 until his death. Lambert denounced Pepin's liaison with his mistress Alpaida, the mother of Charles Martel. The bishop was murdered during the political turmoil that developed when various families fought for influence as the Merovingian dynasty gave way to the Carolingians. He is considered a martyr for his defence of marriage. His feast day is September 17.

Lambert was from a noble family of Maastricht, the supposed son of Apre, lord of Liège, and his wife Herisplende, both from noble families. The child was baptized by his godfather, the local bishop, Remaclus, and educated by Landoald, archpriest of the city. Lambert was also related to the seneschal Hugobert, father of Plectrude, Pepin of Herstal's lawful wife and thus an in-law of hereditary mayors of the palace who controlled the Merovingian kings of Austrasia.

Lambert appears to have frequented the Merovingian court of King Childeric II, and was a protégé of his uncle, Theodard, who succeeded Remaclus as bishop of Maastricht. He is described by early biographers as “a prudent young man of pleasing looks, courteous and well-behaved in his speech and manners, well-built, strong, a good fighter, clear-headed, affectionate, pure and humble, and fond of reading.” When Theodard was murdered soon after 669, the councillors of Childeric made Lambert bishop of Maastricht.[1]

After Childeric himself was murdered in 675, the faction of Ebroin, majordomo of Neustria and the power behind that throne, expelled him from his see, in favor of their candidate, Faramundus. Lambert spent seven years in exile at the recently founded Abbey of Stavelot(674–681). With a change in the turbulent political fortunes of the time, Pepin of Herstal became mayor of the palace and Lambert was allowed to return to his see.[2]

In company with Willibrord, who had come from England in 691, Lambert preached the gospel in the lower stretches of the Meuse, in the area to the north. In conjunction with Saint Landrada he founded a female monastery at Munsterblizen.[3] Lambert was also the spiritual director of the young noble Hubertus, eldest son of Bertrand, Duke of Aquitaine. Hubertus would later succeed Lambert as bishop of Maastricht.[1]

Lambert seems to have succumbed to the political turmoil that developed when various clans fought for influence as the Merovingian dynasty gave way to the Carolingians. Historian Jean-Louis Kupper says that the bishop was the victim of a private struggle between two clans seeking to control the Tongres-Maastricht see.[4] Lambert is said to have denounced Pepin's adulterous liaison with Alpaida, who was to become the mother of Charles Martel. This aroused the enmity of either Pepin, Alpaida, or both. The bishop was murdered at Liege by the troops of Dodon, Pepin's domesticus (manager of state domains), father or brother of Alpaida. The year of his death is variously given for some time between 705 and 709.[5] Lambert came to be viewed as a martyr for his defence of marital fidelity.[2] Lambert's two nephews, Peter and Audolet, were also killed defending their uncle. They too, were viewed as saints.[6]

Although Lambert was buried at Maastricht, his successor as bishop, Hubertus, translated his relics to Liège, to which the see of Maastricht was eventually moved. To enshrine Lambert's relics, Hubertus, built a basilica near Lambert's residence which became the true nucleus of the city. The shrine became St. Lambert's Cathedral, destroyed in 1794. Its site is the modern Place Saint-Lambert. Lambert's tomb is now located in the present Liège Cathedral. The Cathedral of Our Lady and St. Lambert in Liege was built in his honor.

St. Hildegard, also known as St. Hildegard of Bingen and Sibyl of the Rhine, is a Doctor of the Church. She was also a writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, and German Benedictine abbess. She was born around 1098 to a noble family as the youngest of ten children.

Her parents had promised their sick daughter to God, so they placed her in care of a Benedictine nun, Blessed Jutta, in the Diocese of Speyer at 8-years-old. She was taught how to read and sing the Latin psalms. Her holiness and strong piety made her adored by all who met her. It is said, from this young age, Hildegard began experiencing her visions.

When Hildegard turned 18, she became a Benedictine nun at the Monastery of St. Disibodenberg. After Jutta died in 1136, Hildegard was elected superior.

Her unique nature and strong devotion to the Holy Spirit attracted many novices to the convent. The rapid growth alarmed Hildegard. She soon moved on with eighteen other sisters to found a new Benedictine house near Bingen in 1148 and later establish a convent in Eibingen in 1165. She believed this was Divine command.

Hildegard quickly became recognized for her immense knowledge of all things faithful, music and natural science, with knowledge of herbs and medicinal arts, despite never having any formal education and not knowing how to write.

Much of her insight is believed to have been communicated by God himself through her frequent visions. At first, Hildegard did not want to make her visions public, but she would confide in her spiritual director. He passed on the knowledge to his abbot, who decided to assign a monk to document everything Hildegard saw.

Her accounts were later submitted to the bishop, who acknowledged them as being truly from God. Her visions were then brought to Pope Eugenius III with a favorable conclusion.

Hildegard's fame began to spread all throughout Europe. People traveled near and far to hear her speak and to seek help from her, even those who were not common people paid Hildegard a visit.

For remainder of her life, Hildegard continued her writings. Her principle work is called Scivias. Twenty-six of her visions and their meanings are recorded. Hildegarde wrote on many other subjects, too. Her works included commentaries on the Gospels, the Athanasian Creed, and the Rule of St. Benedict, as well as Lives of the Saints and a medical work on the well-being of the body.

Hildegard also became an important person in the history of music. There are more chant compositions surviving by St. Hildegard than any other medieval composer.

The last year of St. Hildegard's life was difficult for her and her convent. Going against the wishes of diocesan authorities, Hildegard refused to remove the body of a young man buried in the cemetery attached to her convent. The boy had previously been excommunicated, but since he received his last sacraments before dying, Hildegard felt he had been reconciled to the Church.

Her actions forced her convent to be placed under an interdict by the Bishop and chapter of Mainz. Months would pass before the interdict was lifted and Hildegard died on September 17, 1179, before the interdict was lifted. She was buried in the church of Rupertsburg. When the convent was destroyed in 1632, her relics were moved to Cologne and then to Eibingen.

After her death, she became even more venerated than she was in her life. According to her biographer, Theodoric, she was always a saint and through her intercession, many miracles occurred.

St. Hildegard became one of the first people the Roman canonization process was officially applied to. It took quite some time in the beginning stages, so she remained beatified.

On May 10, 2012, Pope Benedict XVI gave St. Hildegard an equivalent canonization, and laid down the groundwork for naming her a Doctor of the Church. Five months later, she officially became a Doctor of the Church, making her the fourth woman of 35 saints to be given that title by the Roman Catholic Church. Pope Benedict XVI called Hildegard, "perennially relevant" and "an authentic teacher of theology and a profound scholar of natural science and music."

St. Hildegard's feast day is celebrated on September 17.

Martyr of Vietnam, an ordained priest. A native Vietnamese, he joined the army but was ordained and worked under the auspices of the Foreign Mission of Paris. While visiting his mother, he was arrested in the anti-Christian persecution and martyred by beheading. Emmanuel was canonized in 1988.

The Vietnamese Martyrs (Vietnamese: Các Thánh Tử đạo Việt Nam), also known as the Martyrs of Annam, Martyrs of Tonkin and Cochinchina, Martyrs of Indochina, or Andrew Dung-Lac and Companions (Anrê Dũng-Lạc và các bạn tử đạo), are saints on the General Roman Calendar who were canonized by Pope John Paul II. On June 19, 1988, thousands of overseas Vietnamese worldwide gathered at the Vatican for the Celebration of the Canonization of 117 Vietnamese Martyrs, an event chaired by Monsignor Tran Van Hoai. Their memorial is on November 24 (although several of these saints have another memorial, as they were beatified and on the calendar prior to the canonization of the group).

The Vatican estimates the number of Vietnamese martyrs at between 130,000 and 300,000. John Paul II decided to canonize those whose names are known and unknown, giving them a single feast day.

The Vietnamese Martyrs fall into several groupings, those of the Dominican and Jesuit missionary era of the 18th century and those killed in the politically inspired persecutions of the 19th century. A representative sample of only 117 martyrs—including 96 Vietnamese, 11 Spanish Dominicans, and 10 French members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society (Missions Etrangères de Paris (MEP))—were beatified on four separate occasions: 64 by Pope Leo XIII on May 27, 1900; eight by Pope Pius X on May 20, 1906; 20 by Pope Pius X on May 2, 1909; and 25 by Pope Pius XII on April 29, 1951.[citation needed] All these 117 Vietnamese Martyrs were canonized on June 19, 1988. A young Vietnamese Martyr, Andrew Phú Yên, was beatified in March, 2000 by Pope John Paul II.

The tortures these individuals underwent are considered by the Vatican to be among the worst in the history of Christian martyrdom. The torturers hacked off limbs joint by joint, tore flesh with red hot tongs, and used drugs to enslave the minds of the victims. Christians at the time were branded on the face with the words "tà đạo" (邪道, lit. "Left (Sinister) religion")[1] and families and villages which subscribed to Christianity were obliterated.[2]

The letters and example of Théophane Vénard inspired the young Saint Thérèse of Lisieux to volunteer for the Carmelitenunnery at Hanoi, though she ultimately contracted tuberculosis and could not go. In 1865 Vénard's body was transferred to his Congregation's church in Paris, but his head remains in Vietnam.[3]

There are several Catholic parishes in the United States, Canada, and elsewhere dedicated to the Martyrs of Vietnam (Holy Martyrs of Vietnam Parishes), one of which is located in Arlington, Texas in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.[4] Others can be found in Houston, Austin, Texas,[5]Denver, Seattle, San Antonio,[6] Arlington, Virginia, Richmond, Virginia, and Norcross, Georgia. There are also churches named after individual saints, such as St. Philippe Minh Church in Saint Boniface, Manitoba.[7]

The Catholic Church in Vietnam was devastated during the Tây Sơn rebellionin the late 18th century. During the turmoil, the missions revived, however, as a result of cooperation between the French Vicar Apostolic Pigneaux de Behaine and Nguyen Anh. After Nguyen's victory in 1802, in gratitude to assistance received, he ensured protection to missionary activities. However, only a few years into the new emperor's reign, there was growing antipathy among officials against Catholicism and missionaries reported that it was purely for political reasons that their presence was tolerated.[8] Tolerance continued until the death of the emperor and the new emperor Minh Mang succeeding to the throne in 1820.

Converts began to be harassed without official edicts in the late 1820s, by local governments. In 1831 the emperor passed new laws on regulations for religious groupings in Viet Nam, and Catholicism was then officially prohibited. In 1832, the first act occurred in a largely Catholic village near Hue, with the entire community being incarcerated and sent into exile in Cambodia. In January 1833 a new kingdom-wide edict was passed calling on Vietnamese subjects to reject the religion of Jesus and required suspected Catholics to demonstrate their renunciation by walking on a wooden cross. Actual violence against Catholics, however, did not occur until the Lê Văn Khôi revolt.[8]

During the rebellion, a young French missionary priest named Joseph Marchand was living in sickness in the rebel Gia Dinh citadel. In October 1833, an officer of the emperor reported to the court that a foreign Christian religious leader was present in the citadel. This news was used to justify the edicts against Catholicism, and led to the first executions of missionaries in over 40 years. The first executed was named Francois Gagelin. Marchand was captured and executed as a "rebel leader" in 1835; he was put to death by "slicing".[8] Further repressive measures were introduced in the wake of this episode in 1836. Prior to 1836, village heads had only to simply report to local mandarins about how their subjects had recanted Catholicism; after 1836, officials could visit villages and force all the villagers to line up one by one to trample on a cross and if a community was suspected of harbouring a missionary, militia could block off the village gates and perform a rigorous search; if a missionary was found, collective punishment could be meted out to the entire community.[8]

Missionaries and Catholic communities were able to sometimes escape this through bribery of officials; they were also sometimes victims of extortion attempts by people who demanded money under the threat that they would report the villages and missionaries to the authorities.[8] The missionary Father Pierre Duclos said:

with gold bars murder and theft blossom among honest people.[8]

The court became more aware of the problem of the failure to enforce the laws and applied greater pressure on its officials to act; officials that failed to act or those tho who were seen to be acting too slowly were demoted or removed from office (and sometimes were given severe corporal punishment), while those who attacked and killed the Christians could receive promotion or other rewards. Lower officials or younger family members of officials were sometimes tasked with secretly going through villages to report on hidden missionaries or Catholics that had not apostasized.[8]

The first missionary arrested during this (and later executed) was the priest Jean-Charles Cornay in 1837. A military campaign was conducted in Nam Dinh after letters were discovered in a shipwrecked vessel bound for Macao. Quang Tri and Quang Binh officials captured several priests along with the French missionary Bishop Pierre Dumoulin-Borie in 1838 (who was executed). The court translator, Francois Jaccard, a Catholic who had been kept as a prisoner for years and was extremely valuable to the court, was executed in late 1838; the official who was tasked with this execution, however, was almost immediately dismissed.[8]

A priest, Father Ignatius Delgado, was captured in the village of Can Lao (Nam Định Province), put in a cage on public display for ridicule and abuse, and died of hunger and exposure while waiting for execution; [1] the officer and soldiers that captured him were greatly rewarded (about 3 kg of silver was distributed out to all of them), as were the villagers that had helped to turn him over to the authorities.[8] The bishop Dominic Henares was found in Giao Thuy district of Nam Dinh (later executed); the villagers and soldiers that participated in his arrest were also greatly rewarded (about 3 kg of silver distributed). The priest, Father Joseph Fernandez, and a local priest, Nguyen Ba Tuan, were captured in Kim Song, Nam Dinh; the provincial officials were promoted, the peasants who turned them over were given about 3 kg of silver and other rewards were distributed. In July 1838, a demoted governor attempting to win back his place did so successfully by capturing the priest Father Dang Dinh Vien in Yen Dung, Bac Ninh province. (Vien was executed). In 1839, the same official captured two more priests: Father Dinh Viet Du and Father Nguyen Van Xuyen (also both executed).[8]

In Nhu Ly near Hue, an elderly catholic doctor named Simon Hoa was captured and executed. He had been sheltering a missionary named Charles Delamotte, whom the villagers had pleaded with him to send away. The village was also supposed to erect a shrine for the state-cult, which the doctor also opposed. His status and age protected him from being arrested until 1840, when he was put on trial and the judge pleaded (due to his status in Vietnamese society as both an elder and a doctor) with him to publicly recant; when he refused he was publicly executed.[8]

A peculiar episode occurred in late 1839, when a village in Quang Ngai province called Phuoc Lam was victimized by four men who extorted cash from the villagers under threat of reporting the Christian presence to the authorities. The governor of the province had a Catholic nephew who told him about what happened, and the governor then found the four men (caught smoking opium) and had two executed as well as two exiled. When a Catholic lay leader then came to the governor to offer their gratitude (thus perhaps exposing what the governor had done), the governor told him that those who had come to die for their religion should now prepare themselves and leave something for their wives and children; when news of the whole episode came out, the governor was removed from office for incompetence.[8]

Many officials preferred to avoid execution because of the threat to social order and harmony it represented, and resorted to use of threats or torture in order to force Catholics to recant. Many villagers were executed alongside priests according to mission reports. The emperor died in 1841, and this offered respite for Catholics. However, some persecution still continued after the new emperor took office. Catholic villages were forced to build shrines to the state cult. The missionary Father Pierre Duclos (quoted above) died in prison in after being captured on the Saigon river in June 1846. The boat he was traveling in, unfortunately contained the money that was set for the annual bribes of various officials (up to 1/3 of the annual donated French mission budget for Cochinchina was officially allocated to 'special needs') in order to prevent more arrests and persecutions of the converts; therefore, after his arrest, the officials then began wide searches and cracked down on the catholic communities in their jurisdictions. The amount of money that the French mission societies were able to raise, made the missionaries a lucrative target for officials that wanted cash, which could even surpass what the imperial court was offering in rewards. This created a cycle of extortion and bribery which lasted for years.[8]

Those whose names are known are listed below:

Please keep in mind that these are the anglicized versions of their names

Martyr of Phrygia. Ariadne was a slave in the household of a Phrygian prince. When pagan rites were performed in honor of the prince's birthday, she refused to take part. hunted by the authorities, she entered a chasm in a ridge. The chasm opened miraculously before her and closed behind her, providing her with a tomb.

Saint Ariadne of Phrygia (died 130 AD) is a 2nd-century Christian saint. According to legend, she was a slave in the household of a Phrygian prince. She refused to participate in rites to a pagan god as part of the prince's birthday celebration. As she was fleeing the Roman authorities, she fell through a chasm in a ridge and was entombed.[

Virgin martyr, a patroness of a region in Aragon, Spain. Agathoclia was an abused slave who suffered for the faith in a public trial.

Saint Agathoclia (Agathocleia;[1] Spanish: Santa Agatoclia) (d. ~230 AD) is venerated as a patron saint of Mequinenza, Aragón, Spain. Her feast day is September 17.

Tradition states that she was a virginChristian slave owned by two people who had converted to paganism from Christianity, named Nicolas and Paulina. They subjected Agathoclia to regular physical abuse, including whipping and other violence, in an effort to get Agathoclia to renounce her faith. She repeatedly refused to do so.

Her owners then subjected her to a public trial by a local magistrate. There too, she refused to renounce Christianity, which subjected her to savage mangling from the authorities. When she was found guilty, her sentence included having her tongue cut out, a nonfatal injury.

There is some disagreement about how Agathoclia met her death. Some sources say that her mistress Paulina poured burning coals on her neck. Other sources say that she herself was cast into fire.

The town of Mequinenza celebrates festivals in honor of Santa Agatoclia (called simply “La Santa”) from September 16 to 20.[2] There is also a confraternity in the town dedicated to the saint.[3]